About Us

It’s our passion to help others keep things tidy.

Therefore, we have assisted residential and commercial customers to have spaces that are as efficient as possible. That way, our customers can focus on the more important things.

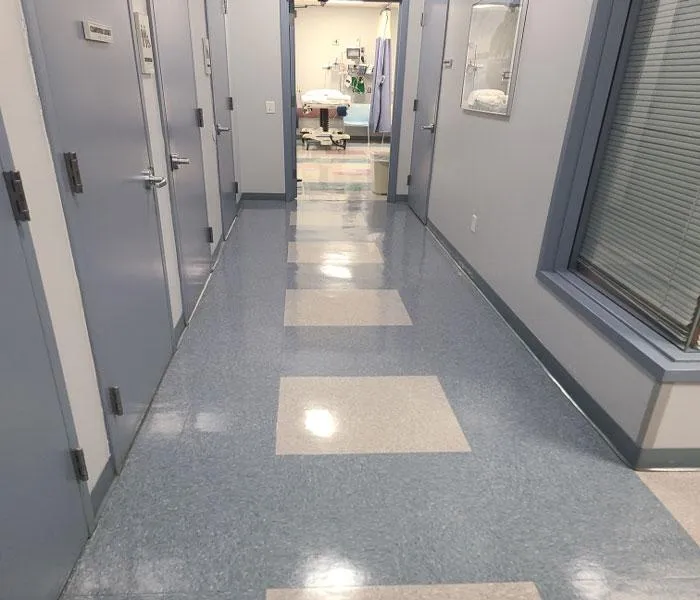

Our commercial cleaning services maximize your productivity by keeping the dust, dirt, and germs around you to a minimum. That way, you can focus on growing your business with less environmental stressors

Our Updates

In the residential space, we’ve helping hundreds of families enjoy their homes without wasting time on the chores that are needed to keep them orderly. You too can spend time with your loved ones without feeling guilty about house cleaning ever again.

We’ll work around your schedule and finish what you’ve contracted us to do in a timely fashion. Since we deliver, we have had the opportunity to serve our commercial and residential customers for 12 years.

Cleaning and Protection

Based on our disinfection protocols, we ensure deep and effective cleaning in all work areas and common areas on your site, minimizing the risk of transmission of harmful viruses. Likewise, we thoroughly clean every area in your home so that you and your family are less likely to get sick.

Our Team

We have a dedicated team of individuals ready to tackle your cleaning needs, no matter the complexity.

Our team is even trained in the clean-up process of blood-borne pathogens in health facilities.

Although we provide janitorial services with ease, we provide the same meticulous eye in our provision of house cleaning services.

So, let us keep your office or home clean and thoroughly disinfected.

View Gallery

Get Quote

Business Hours

Monday to Sunday: Open 24 Hours

+1 888-884-3987

You can connect with us at any time to receive a quote. We will respond in less than 24-hours.

Ads/News

LI business owner shares 12-hour long process to cleanup Jones Beach after the Fourth of July fireworks

4/5/2025 12:00:00 PM

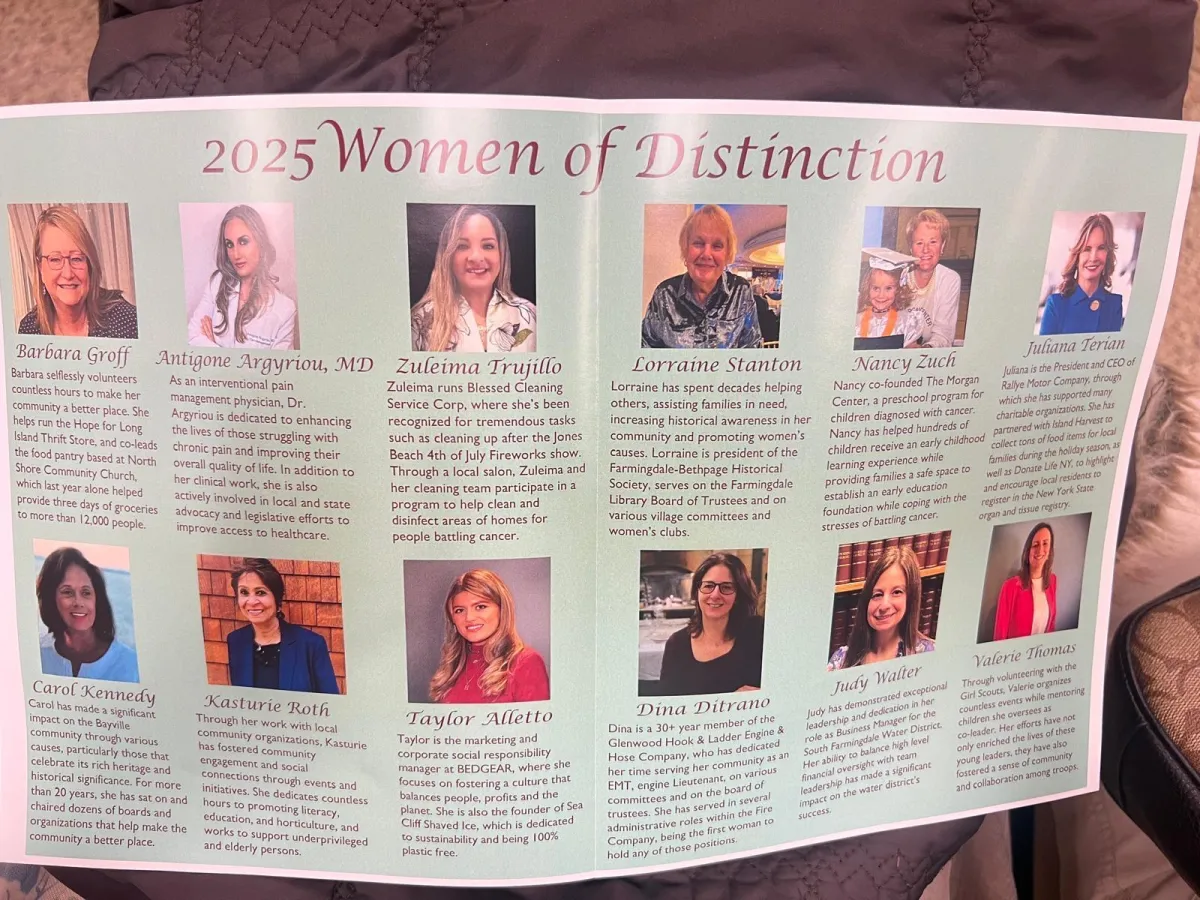

Zuleima Trujillo and her team cleaned Jones Beach overnight after July 4th fireworks, despite heavy trash, rain, and darkness.

GLOBAL RECOGNITION AWARD 2024

4/3/2025 12:00:00 PM

Blessed Cleaning Service, led by Zuleima Trujillo, won a 2024 award for excellence in cleaning services, mentorship, and community impact.

Cleaning and hygiene tips to help keep the COVID-19 virus out of your home

8/19/2020 12:00:00 PM

COVID-19 spreads through respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces, but disinfectants are effective; experts offer tips to protect households.

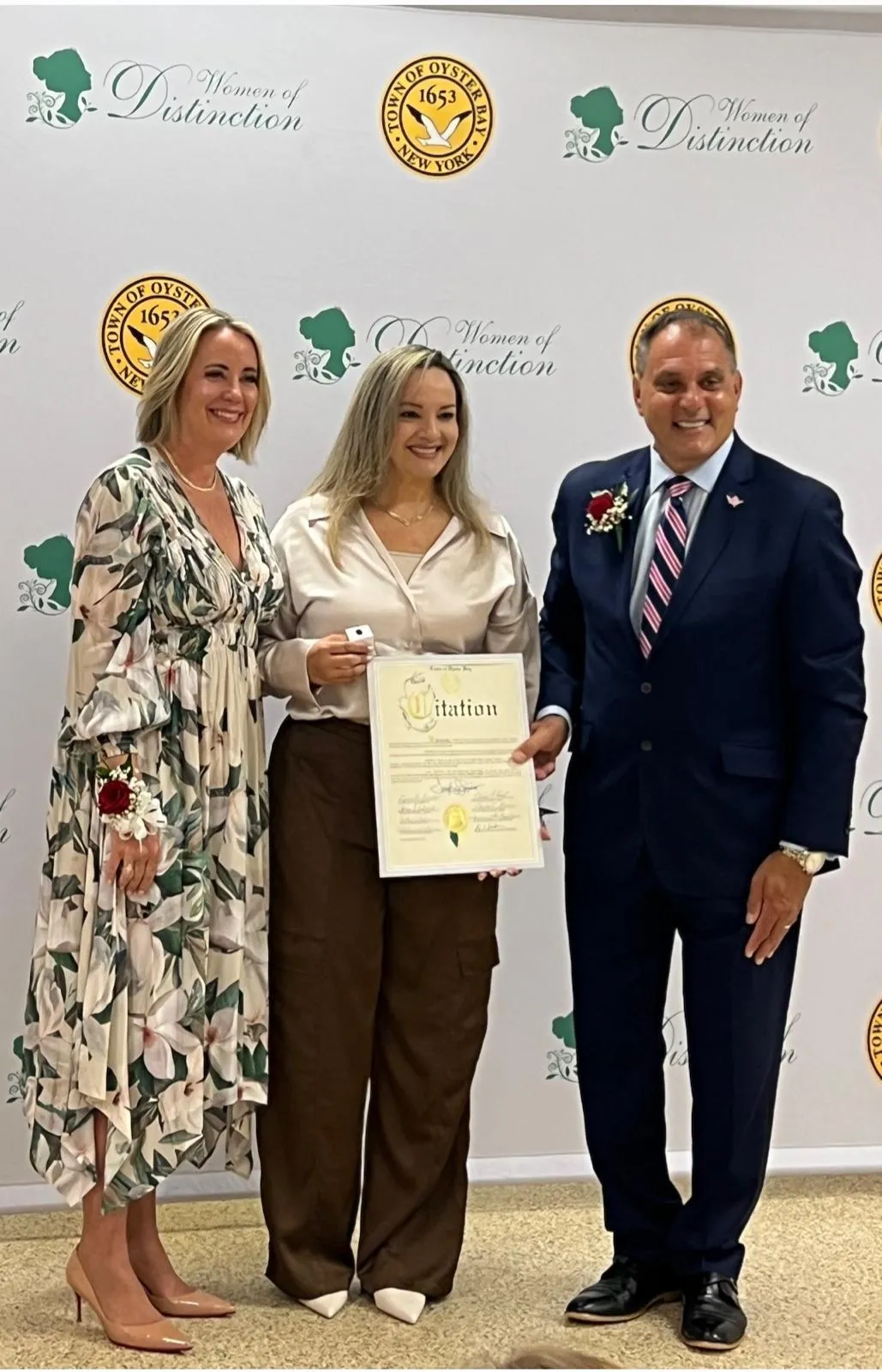

Woman of Distinction 2025 Town of Oyster Bay por el supervisor Joseph Saladiño

Certifications

Testimonial

What People Are Saying

Wonderful. Punctual. 5 came in at 2 pm

Left our house at 5. Focused. Clean.

Detailed. Careful. Cleaned the kitchen

floor that I had tried few times without

success. Can’t wait for their revisit next

month. Ten thumbs up

By: Sergio Isper

Customer

The Best Services In NY.

By: Raul Rivera P.

Customer

They went above and beyond with their attention to detail. The outside of my home looks spotless!

By: Charles M.

Customer

© 2025 Copyright-SocialBoil